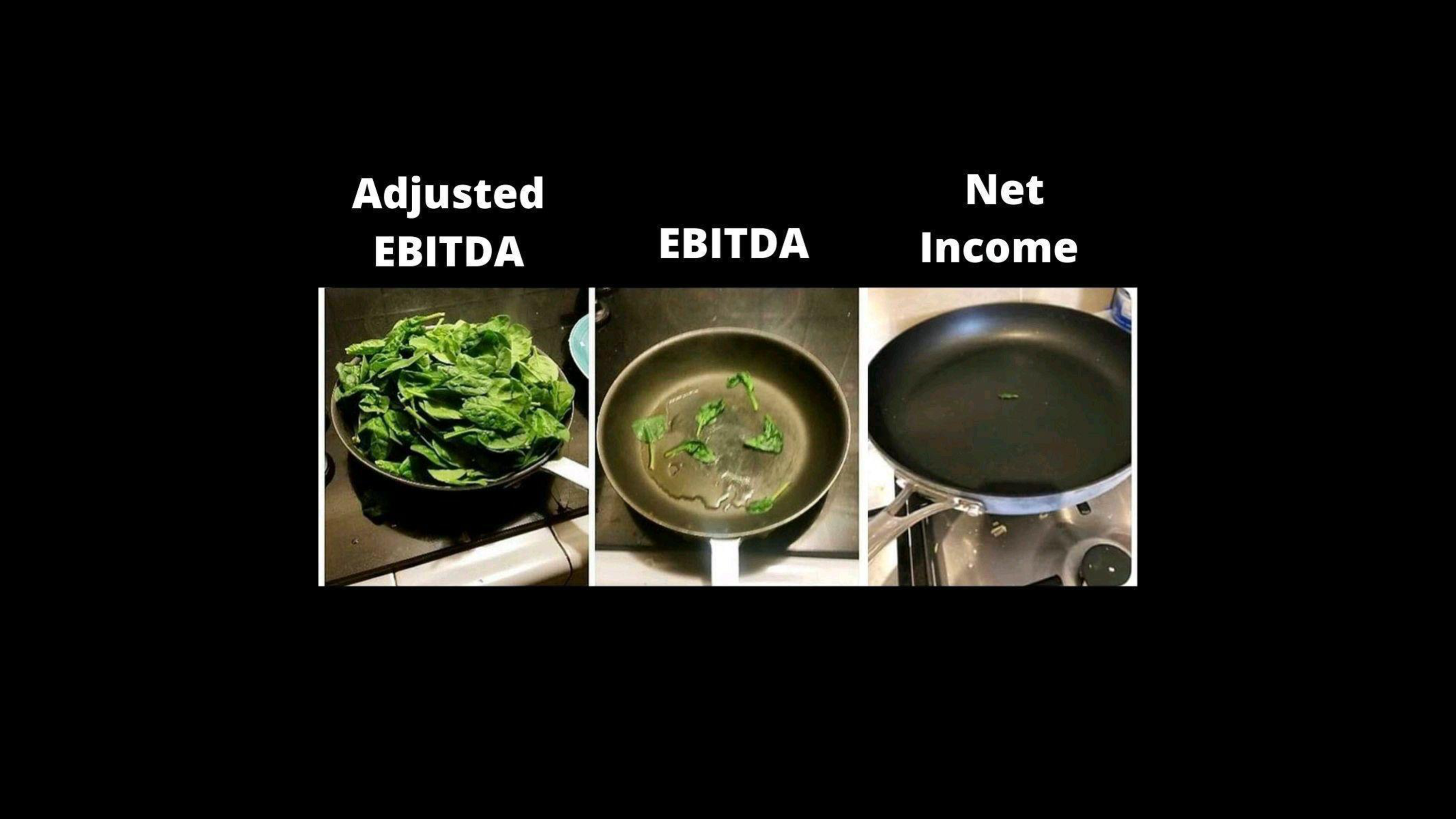

When making investment decisions, it’s common to not rely on raw accounting or GAAP numbers alone. After all, net income is closer to an opinion than a fact.

Reported accounting profits are adjusted by massive publicly traded companies, all the way down to small owner-managed businesses. Adjusted EBITDA is a very popular metric used by the investment community in assessing business performance.

So let’s take a closer look at adjusted EBITDA.

What is adjusted EBITDA

Before understanding “adjusted EBITDA“, let’s briefly go over “EBITDA” first. Here’s a quick explainer from The Sopranos:

EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, amortization, and depreciation) is a short-cut metric in measuring how much cash earnings a business generates annually. You start by taking net profits and then you add back non-cash items (amortization/depreciation), non-operating items (taxes), and financing costs (interest).

EBITDA was first synthesized by John Malone as a way to measure how much cash his business had available to pay down debt (The Outsiders contains a great summary of Malone and his business). EBITDA has since become a widely used metric, especially in private markets. One of its most important use cases is for valuing a business. The vast majority of businesses are sold for a multiple of their annual EBITDA. For example, if a business generates $1m a year in EBITDA, it might be valued 8x that amount, so $8m.

Okay, so what’s adjusted EBITDA?

Making those 4 adjustments to net income often isn’t enough to arrive at a business’s economic profits. There could be several line items that skew a business’s normal operating profits. In many cases, there need to be further adjustments made to EBITDA.

Common EBITDA Adjustments

Any expense or revenue accounted for in EBITDA that is not considered to be “core” or essential to operating the business, can be considered an “adjustment” or “add-back”. Unlike calculating EBITDA, there are no hard and fast rules over what is acceptable and what is not for adjusted EBITDA.

Here are some examples of common EBITDA adjustments:

- One-off events – lawsuits, natural disasters, or anything else that is a one-time event. The adjustment could be to remove the expense from EBITDA.

- Overpaid or underpaid employees – a business can over or under compensate employees. The adjustment here would be to use market rate salaries for key employment positions.

- Personal expenses – many businesses, especially smaller ones, will have the owner’s personal expenses reflected on the P&L. Adding back items such as meals & entertainment, travel, home office and automobile expenses might make sense. In smaller transactions, it’s common for the owner’s salary to also be added back to EBITDA in full to arrive at “seller discretionary earnings” or SDE.

- Other streams of revenue – if a business has other streams of revenue that aren’t connected to the core business, then consider subtracting it from EBITDA.

- Intercompany transactions – if you’re dealing with a business that has mutliple entities, there could be intercompany revenue and expenses that aren’t true economic activity. These should be adjusted for accordingly.

If you want to go further down this rabbit hole, check out this Twitter thread for some more EBITDA “adjustments”:

There is a LONG list of potential adjustments, but the idea is to normalize EBITDA to arrive at annual cash profits, in order to determine a company’s valuation.

Buyer’s perspective

If you’re in the market to acquire a business, you will certainly be presented with adjusted EBITDA figures. Understanding what is an acceptable adjustment is going to take a bit of judgment and knowledge of the overall company and industry.

The seller will likely include as many adjustments as possible to improve their EBITDA and therefore increase the business valuation. When examining each adjustment, always ask yourself “is this really non-core to the operating business I am buying?”.

For example, let’s say legal fees pertaining to a lawsuit were added back to EBITDA, presented as a one-off lawsuit. But what if, the nature of the business/industry was highly litigious, meaning that lawsuits are a normal course of the business operations. In this case, it wouldn’t make sense to adjust EBITDA for legal fees.

Another example, massive sales commissions paid to an employee added back to EBITDA, presented as non-market salary. But what if that employee is critical to the business and was, in fact, going to be sticking around post-transaction. In this case, it wouldn’t make sense to adjust EBITDA for the overcompensated employee.

The bottom line is, as a buyer, you should inspect each adjustment and make your own judgment call on whether it’s non-core to the business or not. The longer you set your timeframe, the more that non-reoccurring expenses start to look like reoccurring expenses.

Seller’s perspective

As an owner and/or seller, you have information asymmetry. You know your business better than anyone else, and therefore should know what adjustments make the most sense.

As good practice, keep regular track of your adjustments, and in turn, your adjusted EBITDA. This way, you’ll always have a sense of what your business is worth.

There are also operating decisions you can make to optimize your EBITDA. For example, if you need new equipment, it might make sense to purchase and finance it instead of leasing it. Purchasing means an asset on your balance sheet and subsequent depreciation expense (which increases your EBITDA instead of leasing costs that are generally not added back). As well, financing means interest expense, which is added back to your net profits to arrive at EBITDA.

Final Thoughts

Given there’s a significant amount of judgment that goes behind an adjusted EBITDA figure, two individuals could easily arrive at a completely different adjusted EBITDA calculation. For this reason, buyers need to dig deep into EBITDA numbers, and potential sellers should track all adjustments in order to have an ironclad rationale for potential buyers. After all, it’s important to get this calculation right and not miss items that could impact the valuation, either positively or negatively.

Hopefully, this post sheds some light on adjusted EBITDA and helps you navigate the metric.

Hi there! I’m Jay Vasantharajah, Toronto-based entrepreneur and investor.

This is my personal blog where I share my experiences building businesses, making investments, managing personal finances, and traveling the world.

Subscribe below, and expect to get a couple of emails a month with some free, valuable, and actionable content.

3 thoughts on “Everything You Need To Know About Adjusted EBITDA”