I read Peter Thiel’s Zero to One years ago but was too young and inexperienced to appreciate some of the key concepts articulated in the book. So I recently re-read parts of the book and wanted to share some important insights, particularly about monopolies.

The book’s intended audience is startups, but I think the concepts are just as applicable to business acquirers – especially those who pursue a growth-through-acquisition strategy. So here’s how the key principles from the book apply to business acquisitions.

Dominate A Small Market

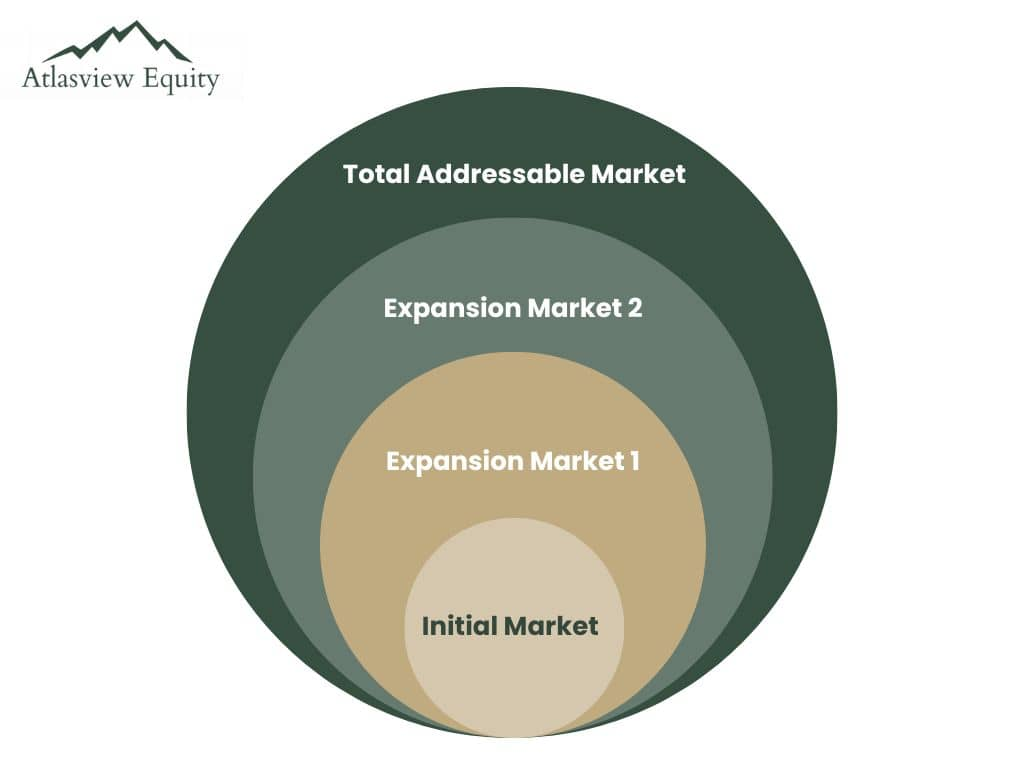

I’ve said this before, and I will say it again – one of the most useless metrics is Total Addressable Market (TAM). Large TAMs have established competitors and are oversupplied with capital so they constantly attract new entrants. This makes it difficult to control market share, even if you have unlimited capital (and full protection from regulators).

As Thiel mentions in the book, you want to pick a small market, with sustained demand, where you can obtain an absurdly high (if not all) market share. Typically these smaller markets are overlooked and undersupplied with capital.

Here are some ways in which small businesses can achieve monopoly-status, or at least, a very high market share:

- Localization – geography can be a moat, especially if you sell physical goods. Larger national players may not be able to economically justify entering a small local geography to compete and small geos naturally detract new entrants.

- Verticalization – hyper-specializing in a single vertical can eliminate direct competition. Solutions, especially if iterated over time, become so tailored to the vertical’s specific nuances that generic competitors are no longer comparable alternatives.

- Specialization – skillset/knowledge of a solution to a niche problem with acute demand. Sometimes there are even required certifications or regulatory barriers to entry.

When people hear “monopoly,” they often think of large, controversial corporations like Microsoft or Google that attract anti-trust scrutiny. However, mini-monopolies exist—they just operate under the radar. These businesses thrive in carefully chosen markets where their position is unchallenged, either because of geography, vertical specialization, or expertise in solving niche problems. These businesses are accessible to, even smaller, acquirers. The key is not to enter a massive market but to identify a small, underserved one where you can dominate and maintain long-term competitive advantages.

P.S. If you want to read case studies on companies with absurdly high market share by picking niche markets, check out the book Hidden Champions.

Expand in Concentric Circles

So you acquired a business with a very high market share in a tiny market. The business enjoys a high level of pricing power, above-average margins, and ample cash flow. The business generates a great ROIC, but since it already has a dominant market share, there are limited growth opportunities in its existing market.

What’s next?

As Thiel mentions in his book, expanding in concentric circles is the logical move. This involves moving into adjacent markets where you can dominate there as well, capturing more of the TAM.

Copart is a great example of achieving this through acquisition. Each junkyard is a mini-monopoly in its local market. Ever since the first junkyard acquisition for $75k, the founder expanded in concentric circles, executing acquisitions to capture the US TAM (which today is a duopoly, with CPRT having an enterprise value of ~$60bn).

The builders of Dye & Durham followed a similar path, by first acquiring OneMove for $5m – conveyancing software focused on the Canadian province of British Columbia, small TAM, but it had a monopoly in BC. From there, they expanded in concentric circles by acquiring dominant conveyancing software in other provinces to capture the entire TAM in Canada (DND’s market share is estimated at 80% with an enterprise value of ~3bn today).

Aggregation is another growth-through-acquisition strategy that follows concentric circle expansion. This strategy involves building a collection of mini-monopolies with the same business model but in different verticals (like Constellation Software), in different geographies (like Thomson Newspapers), or in different specializations (like Transdigm). Each individual business remains decentralized with minimal synergies, but most importantly, maintains its dominant direct market share.

Concluding thoughts

Thiel’s principles from Zero to One about niche market domination and expansion through concentric circles are as applicable to business acquirers as they are to startups. There are lots of mini-monopolies out there that operate in overlooked niche markets. Happy hunting!