I know what you’re thinking. “Not another clickbait-titled Berkshire Hathaway post“. I promise there are some practical tips and tactics for business owners, allocators, and operators in this post, so bear with me!

Here’s how you can turn your small business into a mini Berkshire Hathaway.

Berkshire Hathaway Background

Berkshire Hathaway is a $750bn behemoth of a company. It has large stakes in publicly traded companies, several different operating divisions, and employs hundreds of thousands of employees.

Lost in all its complexity are the core principles that made Berkshire into what it is today.

- Maximize cash from its operating businesses

- Allocate that cash to the best available options

- Compound over the very long term

This may seem grossly oversimplified, but as Munger, himself said: “take a simple idea and take it seriously”. It’s the “take it seriously” part that most people fail to do. That’s what I want to discuss in this post. Let’s take the principles above, and apply them very seriously to your small business.

Step 1: Maximizing Cash

One of the most common ways I’ve seen business owners under-optimize their cash flow is their working capital. Let’s walk through an example.

You’ve been in business for a while now and built great relationships with both your vendors and customers. Invoices show up from your vendors with net 30-day terms but your accounting clerk pays them within 5 days. You give your customers 30 days to pay their invoice, but many of them end up paying a few weeks late. You don’t mind because they always end up paying, so on average, you collect invoice amounts within 45 days.

You keep a healthy $1.5m of cash on hand as a cushion, generate $1.5m in net profits each year, and pay it all out as dividends.

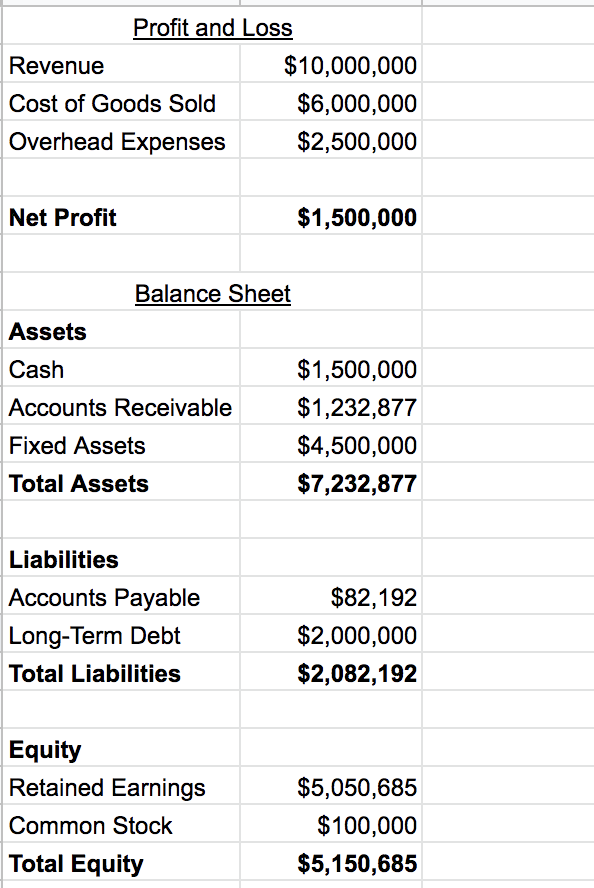

As a result, this is what your profit & loss and balance sheet look like today:

Now, it’s time to take the “maximize cash” idea very seriously. Let’s pull 2 levers here to maximize your cash balance: pay slower & collect faster. You call up your vendors and negotiate an additional 15 days on invoices and you instruct your accounting clerk to pay on the 45th day. You incentivize your customers with a 2% discount if they pay their invoice within 5 days, and they take you up on the offer.

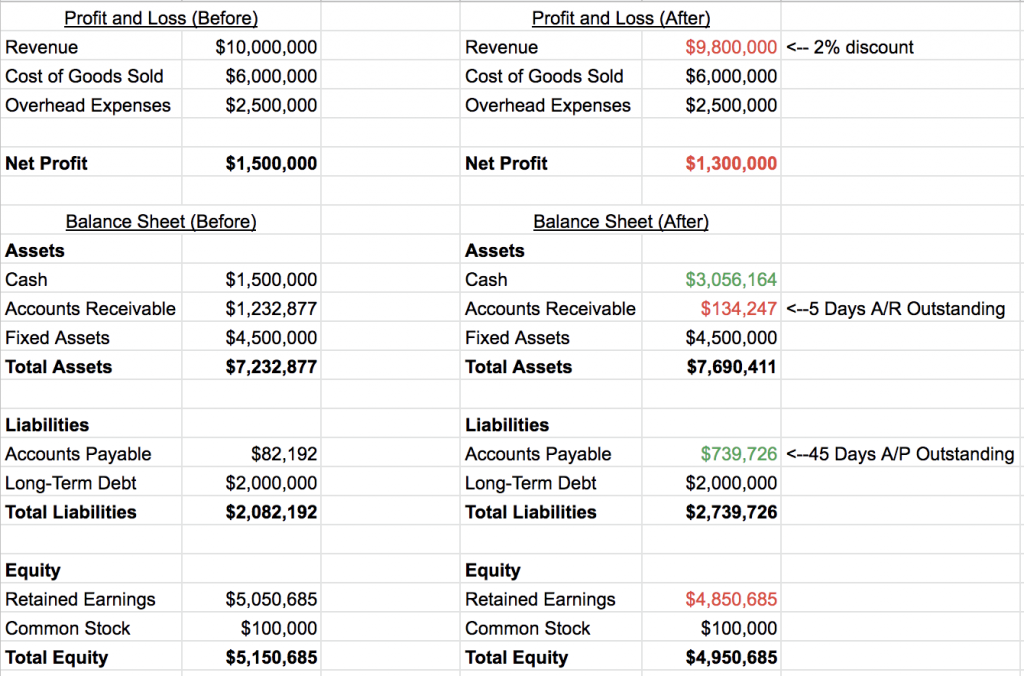

Here’s what your financials look like after implementing these changes:

By collecting faster and paying slower, you’ve sacrificed $200k in net profit, but increased cash balance by $1.75m (net cash increase of $1.55m). Most business owners would balk at the idea of sacrificing profit, but remember, we’re taking “maximize cash” very seriously. As long as your business doesn’t shrink, that increased level of cash float will always exist. And if your business happens to grow, that cash float should expand.

Sidenote: Cash Float

In the above example, we reduced working capital bloat to increase cash float. There are several other levers to pull, beyond just working capital, to increase the cash float in your business. Reducing operating expenses, selling or refinancing assets, and increasing pricing are just some examples.

There are also businesses that naturally have a large cash float, based on the timing difference between cash inflows and outflows. Insurance, Berkshire Hathaway’s core business, is a great example. In insurance, customers give you cash upfront (insurance premiums), but you don’t experience the expenses till later (insurance claims).

This is also why my investment firm, Atlasview Equity, loves enterprise software, as it has similar natural cash float dynamics. Enterprise software customers pay upfront in advance of a year or even several years, and you experience expenses later on.

Businesses with a naturally large cash float supercharge this whole process.

Step 2: Allocating Cash

When Warren Buffett first acquired Berkshire Hathaway in 1965, it was a small textile manufacturing business. The textile industry in the US wasn’t doing too well, as the entire industry was shrinking. It didn’t take long for Buffett to realize that reinvesting Berkshire’s cash back into its operations wasn’t the best use of capital.

Small businesses don’t stay small on purpose. On the macro level, there are external market forces at play that prevent small businesses from experiencing compound growth. On the micro-level, the usual culprit is not enough reinvestment opportunities within the business where incremental returns exceed the cost of capital. If small businesses could easily achieve compound growth organically, they wouldn’t stay small for very long!

Back to our example. By default, you have always reinvested any extra cash back into your business, without consideration of the return on capital. Initiatives like hiring more salespeople, increasing advertising spend, and purchasing more equipment. It’s what you’re used to, and you’ve never even considered anything otherwise. Taking the “allocate cash to the best available option” very seriously, means looking at ALL options, even if they are outside of your business.

With thorough diligence, you’ve concluded that the business won’t grow or shrink and should remain steady at today’s run rate & profitability. And, like Berkshire’s textile firm, incremental returns on reinvesting into your business won’t exceed your cost of capital. That being said, you now have an extra $1.55m in cash that you need to allocate. So let’s look at options outside of your business.

Public Equities

A good starting place is public equities. This is where Berkshire Hathaway started, and to this day they manage a large public equities portfolio. You could allocate the $1.55m into an S&P 500 index fund. It has historically been a safe bet, generating around 9% per annum, adjusted for inflation. This should always be your first question before allocating any capital (either inside or outside of your business): will it return more than the S&P 500?

You could also look at other publicly-traded businesses within your industry. In every supply chain, there is usually one or two businesses that are capturing the lion’s share of value. Identify these businesses, and see if they’re publicly traded. Since you’re obviously familiar with your own industry, you’d have an edge in assessing their businesses.

Alternatively, you could allocate the cash to a completely new industry where you know the returns are much better. This is exactly what Buffett did when he reallocated cash from Berkshire Hathaway (the failing textile firm) to stock of insurance businesses.

Private Equities

Privately-held businesses are also another option. It’s certainly much more difficult compared to investing in stocks, but there could be tremendous upside.

For example, you could acquire competing businesses. Or perhaps suppliers and customers. Depending on your industry, this could unluck significant value, far beyond S&P 500 returns. Many business owners have a bias toward chasing and influencing demand. However, if your industry isn’t growing very fast, reducing and influencing supply (something that consolidation achieves) may be a more effective way to create value.

Acquiring businesses does require expertise in M&A. At Atlasview, I help our portfolio companies navigate this process. If you’re in a fragmented industry and feel that significant value could be created through consolidation, feel free to reach out!

Step 3: Compounding Long Term

Whichever capital allocation option you decide is the best, the final step is holding long-term. Berkshire Hathway is famous for holding its investments for a very long time, sometimes even decades. Taking this final step very seriously, you plan on compounding that $1.55m for at least 25 years.

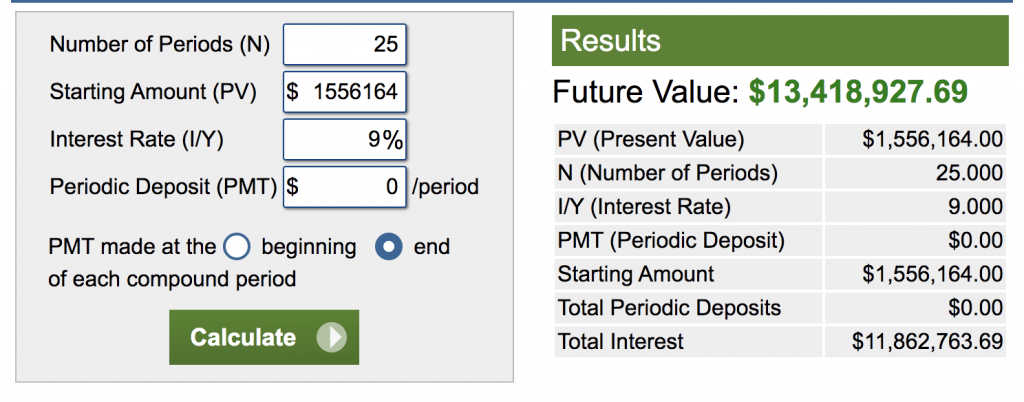

If you allocate that cash to the S&P 500, the value after two and a half decades would be $13.4m

But let’s say, you have a larger risk appetite than an index fund. You are confident in your capital allocation abilities and want to follow in the footsteps of Buffett. So you decide to allocate the cash to individual businesses you understand well. Along the way, you’ve managed to acquire control of other businesses where you’ve rinsed/repeated Steps 1 and 2, amplifying this process.

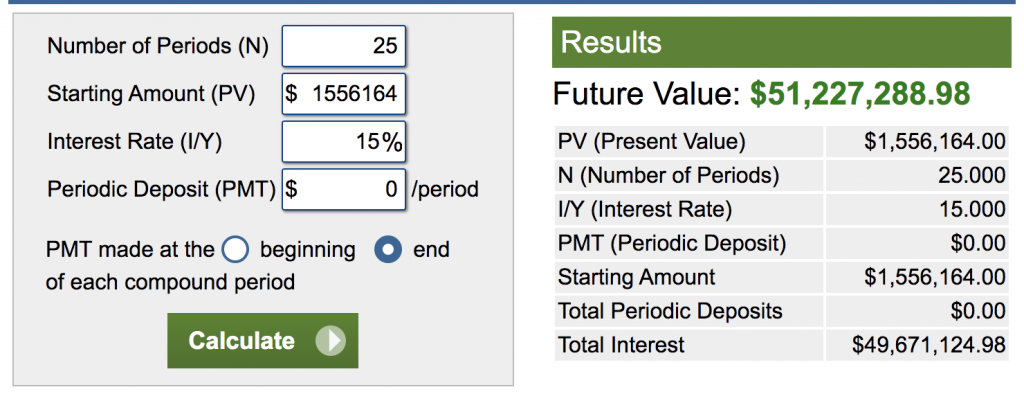

After 25 years, you’ve compounded that $1.55m of extra cash float at 15% per year, resulting in…

That’s quite the result from that extra cash you’ve managed to find in your small business, isn’t it? It’s a great tradeoff considering you sacrificed $200k in annual profits (so a total of $5m after 25 years), to generate $51m in value – over 10x that amount.

So congratulations, you’re now the owner of a diversified investment holding company. You’ve turned your small business into a mini Berkshire Hathaway.

Final Thoughts

The main lesson here is to challenge yourself as a business owner by asking if cash is currently optimized and allocated to the best use. In this example, by reallocating cash that was parked in the working capital of your small business, you’ve created significant value. That’s the power of combining operating prowess, shrewd capital allocation, and thinking in future dollars.

As both an operator of businesses and an allocator of capital, I am constantly assessing cash and where it’s being parked, and I hope this post inspires you to do the same!

Hi there! I’m Jay Vasantharajah, a Toronto-based entrepreneur and investor.

This is my personal blog where I share my experiences managing my portfolio of real estate, stocks, and private companies. I write extensively about allocating capital and building businesses.

Subscribe below, to get a couple of emails a month with free, valuable, and actionable content.

3 thoughts on “How To Turn Your Small Business Into A Mini Berkshire Hathaway”